Building Your First AR-15: Step-by-Step DIY Guide | AmmoJo.com

Posted by Ammojo on Jun 23rd 2025

Building Your First AR-15 is a comprehensive step-by-step manual for legally assembling an AR-15 rifle using commercially available parts. This guide is structured for three experience tiers – Beginner, Intermediate, and Expert – with detailed instructions, diagrams, checklists, real-world build examples, best practices, and safety tips at each level. Whether you’re a first-time builder or a seasoned gunsmith, this eBook will help you build a reliable AR-15 while staying safe and compliant with the law.

Introduction

Building an AR-15 is an engaging way to understand your firearm inside and out. At its core, the AR-15 is a modular, semi-automatic rifle comprised of two main sections: the upper receiver and the lower receiver. Each section contains various components that together make a functioning firearm. In this introduction, we’ll cover AR-15 basics, the tools you’ll need, and how this guide is organized. We’ll also touch on safety and legal considerations before you start your build.

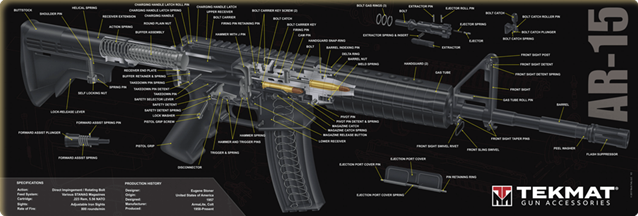

Overview of AR-15 Components. This diagram labels major parts of an AR-15, including the upper receiver group (barrel, handguard, bolt carrier group, charging handle, forward assist, etc.) and the lower receiver group (trigger, pistol grip, magazine well, stock, buffer tube, etc.

Understanding these parts is crucial before assembly.

AR-15 Basics

The AR-15 rifle is often called a “platform” because of its modularity and vast options for customization. It operates on a direct impingement gas system, meaning gas from a fired cartridge is siphoned from the barrel through a gas tube to cycle the action (more on gas systems in a dedicated chapter). The rifle is divided into two primary assemblies:

- Lower Receiver Group: The serialized part of the firearm (legally the “firearm” itself) housing the trigger mechanism (fire control group), magazine well, and buttstock. It’s often called the “brain” of the rifle because it contains the trigger and controls. The lower receiver interfaces with parts like the trigger, magazine catch, bolt catch, safety selector, pistol grip, and stock.

- Upper Receiver Group: The upper portion houses the bolt carrier group (the “heart” of the rifle) and the barrel, and it attaches to the lower via two pins. The upper receiver group includes the bolt carrier and bolt (which chamber, fire, and eject rounds), the charging handle for manual cycling, the barrel, and its components (gas block, gas tube, muzzle device), handguards, and sights or optics.

Each part of the AR-15 can be purchased separately and assembled, which is why building one is feasible for enthusiasts. Be aware that the lower receiver (even as a stripped part) is legally considered a firearm, so it must be transferred through the proper legal channels (FFL) with a serial number. All other parts can usually be bought freely online or in stores, but certain configurations may be restricted by state laws (discussed in the Legal Appendix).

Tools and Workspace

Before diving in, gather the necessary tools and prepare a safe workspace. Building an AR-15 requires only common hand tools and a few specialized armorer tools to make the job easier:

- Work Surface: A sturdy table or bench with good lighting. Consider using a gun vise or blocks to hold the receivers steady during work.

- Safety Gear: Safety glasses (especially important during spring-loaded parts installation), and ideally ear protection if you’ll be doing functions checks with snap caps or dry firing.

- Basic Hand Tools: A set of brass or steel punches (for tapping in small pins), a small hammer (with plastic or rubber head to avoid marring finishes), a set of hex keys/Allen wrenches, and a flat-head screwdriver. Many AR-15 parts use hex screws or small pins.

- Needle-nose pliers or tweezers: Helpful for holding tiny springs and detents.

- Masking tape: Can protect the receiver from scratches when pounding in pins (taping around the pin holes).

- Torque Wrench: Recommended for tightening the barrel nut and possibly the muzzle device to specified torque. A torque wrench ensures you don’t under- or over-tighten critical components.

- Armorer’s Wrench (Combo Tool): A specialized multi-tool for AR-15 that usually includes a barrel nut wrench, castle nut wrench for the buffer tube, and other functions. This is very useful especially for the upper receiver assembly and installing the buffer tube.

- Vise and Receiver Blocks: While not strictly required for a basic build, a bench vise with vise blocks (plastic inserts) for the upper and lower receiver can greatly help by securing the firearm while torquing parts (like the barrel nut or muzzle device). For beginners without a vise, it’s still possible to assemble using careful manual pressure and support, but a vise is strongly recommended for the upper assembly.

- Castle Nut Wrench: If not included in your armorer’s tool, you’ll need a wrench for the castle nut (the nut that locks down the buffer tube). Most combo tools have this.

- Roll Pin Holders/Starter Punches: These are optional specialized tools that hold small roll pins to get them started straight. Beginners may find these very helpful for frustrating pins like the bolt catch pin.

- Clevis pin or “Pivot Pin Tool”: A simple clevis pin or dedicated tool can help install the front takedown pin detent without launching it across the room (a common beginner headache).

- C-Clamp (small): Handy for compressing the trigger guard ears when installing the trigger guard roll pin to prevent slipping and causing the ear to snap off. A 4-inch C-clamp is suggested.

- Utility Knife: Useful for certain tricks like using the razor blade method to hold down the pivot pin detent when installing it.

Parts & Components Needed: In the chapters that follow, each section will detail the specific parts needed for that assembly (lower parts, upper parts, etc.) along with a checklist. At a high level, a complete AR-15 build will require:

- A Stripped Lower Receiver (the serialized frame) and a Lower Parts Kit (LPK) containing all internal lower parts (trigger, hammer, springs, pins, magazine catch, bolt catch, etc.).

- A Buffer Assembly (buffer tube, buffer spring, buffer weight, and receiver end plate & castle nut) and a Stock (buttstock that fits your buffer tube, either mil-spec or commercial spec tube).

- A Stripped Upper Receiver and Upper Parts (ejection port cover, forward assist assembly).

- A Barrel, Gas Block, and Gas Tube of appropriate length for the barrel.

- A Bolt Carrier Group (BCG) and Charging Handle.

- A Handguard (fore-end rail or grips) that is compatible with your barrel mounting (either fits a standard barrel nut or a proprietary system if you use a certain free-float handguard).

- Muzzle Device (flash hider, muzzle brake, or compensator) and a crush washer or shims for timing it.

- Sights/Optics and any desired accessories (grips, slings, lights, etc.).

Don’t worry if this seems like a lot – we will break down each of these in their respective chapters. Also note that you can buy some of these parts pre-assembled (for example, many first-timers buy a complete upper receiver that has the barrel, gas system, and handguard already assembled, which can simplify the build). However, this guide will teach you how to assemble everything from scratch for maximum learning.

Safety Notes

Always practice safety when working on firearms. Before working on any gun or component, ensure it is unloaded and no ammunition is present in the workspace. When you eventually test-fire your AR-15, follow all gun safety rules. During assembly, some parts like springs are under tension and can fly out – wear eye protection. Keep track of small parts (a magnetic tray or small containers help so you don’t lose springs/detents).

After assembly, always perform a thorough function check in a safe environment with the firearm unloaded. We will cover function checks in the troubleshooting chapter. This ensures the rifle operates correctly (trigger resets, safety engages, magazine locks, bolt cycles, etc.) before any live firing.

Legal Considerations (Brief Overview)

Building an AR-15 is legal for most U.S. civilians federally, but you must use a serialized lower receiver (unless you comply with regulations for manufacturing one privately, which is beyond our scope). All parts used must be legal – no full-auto components or anything that would make the firearm illegal. We will include a detailed Legal Appendix at the end with state-by-state restrictions because many states have specific laws (for example, bans on certain features or magazine capacities). Make sure you read that section and understand your local laws before building. For instance, some states like California, New York, New Jersey, etc., have assault weapon bans that may prohibit a standard AR-15 configuration, requiring modification (like fixed magazines or featureless builds). Other states may allow possession of AR-15s but have magazine capacity limits (e.g., 10-round limits) or require a license. We’ll cover these in the appendix.

One federal consideration: if you plan a short-barreled rifle (SBR) (barrel <16"), that falls under the NFA (National Firearms Act) and requires a tax stamp and paperwork before you build. This guide assumes a 16" or longer barrel for a rifle. You can legally build an AR-15 pistol (barrel <16" but without a stock – using a pistol brace if allowed, or bare buffer tube) without a tax stamp, but many areas have changing laws on pistol braces. For simplicity, we focus on rifle builds (16"+ barrels with a stock). If you do choose a barrel shorter than 16", you must either register it as an SBR before building or build it as a pistol (no stock) – check all applicable laws. Generally, it’s easiest for a first build to stick with a 16" or 18" barrel to avoid these issues.

Now that you have an overview, let’s dive into the build process chapter by chapter. Each chapter is organized by component group (lower receiver, upper receiver, etc.) and subdivided into Beginner, Intermediate, and Expert sections. The Beginner sections assume this is your first build and you are using mostly standard parts with minimal modifications. Intermediate sections introduce upgrades or alternative methods to enhance your build once you have basic experience. Expert sections delve into advanced techniques and fine-tuning (for accuracy, high-end performance, or custom configurations). Feel free to follow the level that matches your comfort and read the others to learn more. Even if you’re a beginner, reading the Expert tips will give you insight into what’s possible as you gain skill.

Throughout the guide, we’ll also provide real-world examples of parts choices for budget, mid-tier, and premium builds. These examples illustrate how a build can be done economically versus a no-expense-spared approach, and what trade-offs come with each. Look for the “Build Example” callouts in each chapter for these comparisons.

Let’s get started with the foundation of your rifle – the Lower Receiver Assembly.

Lower Receiver Assembly

The lower receiver is the serialized core of the AR-15. It’s a frame that houses the trigger and firing mechanism, controls (safety selector, magazine release, bolt catch), and supports the stock and buffer system. This section will guide you through assembling a stripped lower receiver with a lower parts kit and attaching the buffer tube and stock. We’ll cover three skill levels:

- Beginner: Basic assembly using a standard lower parts kit and mil-spec components.

- Intermediate: Installing enhanced parts like an upgraded trigger, ambidextrous controls, or anti-roll pins.

- Expert: Advanced lower work such as tuning trigger pull, installing a drop-in match trigger, or fitting an 80% lower (if legally allowed in your area), as well as tips for improved reliability and performance.

But first, let’s gather what we need.

Parts and Tools Checklist – Lower Receiver

Parts Needed:

- Stripped Lower Receiver: This can be made of forged aluminum (most common), billet, or polymer. For beginners, a standard forged lower (e.g., from Anderson, Aero Precision, PSA, etc.) is cost-effective. Ensure it’s compatible with “mil-spec” parts. (Mil-spec is the military specification, and most AR-15 parts adhere to it, meaning cross-compatibility).

- Lower Parts Kit (LPK): A complete LPK includes the trigger, hammer, springs, pins, and all small parts to complete the lower. It often includes a pistol grip as well. Some LPKs come without trigger group if you plan to install an aftermarket trigger – so choose accordingly.

- Trigger Group: If you’re not using the stock trigger from the LPK, you’ll need a trigger kit. Beginners can use the included mil-spec trigger (typically ~5-8 lb. pull weight). Intermediate/Expert might have a drop-in trigger upgrade (like a Geissele, CMC, etc.).

- Buffer Kit: This includes the buffer tube (also called receiver extension), buffer spring, buffer weight, end plate, and castle nut. Choose a carbine buffer tube (typical for collapsible stocks) or an A2 rifle buffer tube (for fixed full-length stocks) depending on your stock. The buffer weight can be standard (3 oz carbine buffer) for starters.

- Stock: The buttstock that fits your buffer tube. For a carbine buffer tube, you’ll use an adjustable/collapsible stock. For example, a Magpul MOE or CTR stock is popular. For rifle tubes, an A2 fixed stock or Magpul PRS for precision. Beginners often choose a basic collapsible M4-style stock for versatility.

- Pistol Grip: Often included in LPK, but you can choose aftermarket grips for better ergonomics. (Magpul MOE, BCM Gunfighter, etc.)

- Optional Upgrades: Ambidextrous safety selector, extended magazine release, anti-rotation trigger pin sets, etc., if you desire (typically intermediate/expert territory).

Tools Needed:

- Punch set (1/16", 5/64", 3/32" sizes cover most AR roll pins).

- Small hammer or mallet.

- Needle-nose pliers (useful for springs/detents).

- Castle nut wrench (for tightening the buffer tube’s castle nut).

- Flathead screwdriver (for pistol grip screw, if slotted screw is used; some grips use an Allen head screw instead).

- Allen keys (if your grip screw or aftermarket parts use hex screws).

- Receiver vise block (optional but helpful to hold the lower, though many install the LPK with the lower just lying on a bench).

- Masking tape (to protect finish around pin holes).

- Intermediate/Expert tools: If installing certain upgrades: a torque wrench (for torquing the castle nut to spec ~40 ft-lbs.), a small file or sandpaper (if minor fitting of aftermarket parts is needed), and a trigger pull scale (if measuring trigger weight for tuning).

Now we’ll proceed to assembly. Safety Tip: As you assemble, small springs and detents (like the takedown pin detents or safety detent) can launch out and disappear. Work slowly, control springs with your finger or a tool, and wear eye protection.

Beginner: Lower Receiver Assembly Step-by-Step

Follow these steps to assemble a standard AR-15 lower receiver with a mil-spec lower parts kit:

- Prepare the Lower & Work Area: Secure the stripped lower receiver on your bench (use a vise block if available). Ensure you have all LPK components laid out. It helps to identify each part first. Refer to an exploded diagram of the AR-15 lower to recognize parts (trigger vs. hammer, springs, detents, etc.). See image below for a typical LPK layout.

Lower Parts Kit Components. A typical AR-15 lower parts kit includes the trigger and hammer (bottom left), disconnector, springs, pins, bolt catch, magazine catch, safety selector, detents, buffer retainer, etc. Keeping these organized will make assembly easier. (Candy not included!)

- Install the Magazine Catch: This is usually the easiest step and a good starting point. Locate the magazine catch button, the magazine catch shaft, and the magazine catch spring.

- Insert the magazine catch shaft (with threaded end) into the round hole on the right side of the receiver (above the trigger opening).

- On the left side, place the spring over the protruding shaft, then press the magazine catch button on top of the spring into the recess on the left side.

- While pressing the button in (so it’s below flush), rotate the magazine catch shaft clockwise (from the right side) to thread it into the button. Continue until the end of the shaft is flush with or slightly past the button face when the button is released.

- Function check: Press the mag catch button – the catch on the other side should retract. This will later hold the magazine. Tip: Beginners sometimes scratch the receiver here – protect the receiver with tape, and you can use a plastic pen to push the button deep so you can rotate the catch without scraping the receiver.

- Install the Bolt Catch: The bolt catch is the lever on the left side that locks the bolt open on an empty magazine. The bolt catch assembly has a small bolt catch spring, a plunger (bolt catch buffer), and the bolt catch lever itself with its roll pin.

- First, drop the small spring into the hole on the left side of the receiver by the magazine well (just below the catch’s pivot point). Then drop the tiny plunger on top of the spring (rounded end outwards).

- Place the bolt catch lever in position – align its hole with the holes in the receiver ears. Ensure the plunger and spring stay in their hole pressing against the catch.

- IMPORTANT: Tape around the area to prevent scratching the receiver. The bolt catch roll pin installs from front to rear (check your receiver’s holes; usually one side is slightly countersunk – start from that side).

- Use a roll pin holder or needle-nose pliers to start the roll pin into the hole. Gently tap it in with the hammer and punch until it goes through the catch’s hinge and is flush. Go slowly and ensure the catch moves freely and the pin doesn’t kink. This is one of the trickier steps – patience is key. If it’s very tight, some builders use specialized tools or even channel-lock pliers with tape to press the pin in.

- Function check: press the top of the bolt catch – it should spring back via the plunger spring.

- Install the Pivot Pin (Front Takedown Pin): The pivot pin is the larger of the two takedown pins and goes at the front of the receiver (just above the magazine area). It is retained by a tiny detent pin and spring from the front. This step is notorious for launching that tiny detent across the room.

- Locate the small hole on the front of the receiver (right side of the pivot pin lug). Insert the tiny spring into this hole first.

- Now comes the tricky part: the detent pin must be inserted and then captured by the pivot pin. One method: Use a razor blade or thin piece of metal to hold the detent in place. Push the detent into the hole on top of the spring (it will stick out a bit, under tension). While holding it down with the razor blade (covering the hole so the detent can’t pop out), slide the pivot pin in from left side partway. The pivot pin has a groove that will capture the detent. Align that groove with the detent’s path.

- When ready, push the pivot pin in, and remove the blade so the detent snaps into the groove. (Alternatively, some use a specialized pivot pin tool or even a 1/4" clevis pin with a hole to trap the detent, then rotate to swap in the actual pin.)

- If done correctly, the pivot pin will now be captured – it shouldn’t pull fully out. It should slide and click as the detent locks it when fully extended.

- Tip: Perform this operation in a large clear plastic bag or aim it into a towel so if the detent flies, you can find it.

- Install the Trigger Group: The fire control group includes the trigger, trigger spring, disconnector, disconnector spring, hammer, hammer spring, and the two trigger/hammer pins.

- Start with the trigger. Fit the small disconnector spring into the trigger (there’s a recess on the trigger’s top for it; the wider end of the spring goes in the trigger). Then place the disconnector on top of the trigger (the spring will push it up) – align the hole in the disconnector with the hole in the trigger.

- Orient the trigger spring on the trigger: the spring’s coils wrap around the trigger pivot area, with the legs of the spring pointing forward and down, resting on the trigger itself (so it will push the trigger upward when installed).

- Now insert the assembled trigger (with disconnector on top, held by your fingers) into the receiver’s trigger well. Align the trigger’s pin hole with the lower receiver holes. Push the trigger pin through the receiver and trigger assembly (some wiggling may be needed). It should go through the disconnector as well, locking it in place. You may gently tap it with a mallet. If holes aren’t aligned, use a small punch as a slave pin to line them up, then push it out with the real pin.

- Next, the hammer: the hammer spring should be installed on the hammer with its coils around the hammer pin area and the legs pointing backwards (toward the buttstock end). The spring’s legs will rest on top of the trigger pin when installed, providing tension.

- Cock the hammer spring legs back and insert the hammer into the receiver (it will be under tension wanting to spring up). Align the hammer’s holes with the receiver holes. Push the hammer pin through to secure it. This may also need some tapping. Ensure the J-pin (a little spring inside hammer) is oriented to hold the pin in place (usually not an issue with standard pins).

- Once both pins are in, function test the trigger group carefully: Hold the hammer with your thumb (so it doesn’t slam forward and damage the receiver). Cock the hammer, then ensure the safety is off and pull the trigger – the hammer should release (catch it with your thumb). With trigger still pressed, re-cock the hammer – it should be caught by the disconnector (not fly forward). When you release the trigger, the hammer should drop from disconnector to be caught by trigger sear (you’ll hear a click – that’s trigger reset). This is the basic trigger function check. Always catch the hammer; do not let it strike the receiver without the upper in place.

- Install the safety selector: Actually, this can be done before the hammer if you prefer. To install the safety, the hammer must be cocked (so it’s out of the way). Simply insert the safety selector lever from the left side of the receiver into its hole (pointing to “fire” position as you insert). It will slide through the trigger area (the trigger must be installed to put it in, otherwise the safety won’t go in – if needed, squeeze the trigger a bit to align). Once through, leave it in “safe” for now (pointing forward).

- On the right side of the receiver, if you have an ambidextrous safety, install the right lever per its instructions (usually a tiny screw). Otherwise, a standard safety has just the one lever.

- Now install the pistol grip: The grip not only provides a handle; it also retains the safety selector spring and detent. Take the tiny safety detent pin (often brass-colored) and drop it into the small hole just behind the trigger, under the safety lever; the pointed end goes upward into the groove on the safety selector. Then the safety detent spring goes into the hole in the pistol grip (usually a hole on top of the grip).

- Carefully align the grip to the receiver, making sure the spring goes into the hole and pushes on the detent. Push the grip fully into place. The spring should now be putting pressure on the detent against the safety selector.

- Secure the grip with the provided screw (up through the bottom of the grip into the receiver). Tighten it snug (not over-tight – if it’s a screw into aluminum, you don’t want to strip it). Typically, either a flathead or hex screw.

- Check the safety: it should now click between Safe and Fire positions with detent resistance. On “Safe,” the trigger should not release the hammer; on “Fire,” it should. Do this check again catching the hammer safely. Never let the hammer strike freely without the upper.

- Install the Buffer Retainer and Spring: Before the buffer tube goes on, install the small buffer retainer pin and its spring. These keep the buffer from flying out when the upper is opened.

- Locate the small hole at the rear of the lower (in the threaded area for the buffer tube). Place the buffer retainer spring in the hole, then the buffer retainer pin on top (small plunger with a rounded top). This will later be captured by the buffer tube as you thread it in.

- Attach the Buffer Tube and Stock: Now you’ll assemble the buffer system onto the lower:

- Thread the castle nut onto the buffer tube (notches toward the receiver). Slip the end plate onto the tube (concave side facing the receiver).

- Begin threading the buffer tube into the back of the receiver by hand. As it gets close to the buffer retainer, you want the tube to capture the retainer pin’s lip. Push down the buffer retainer pin and continue threading the tube just enough to hold the pin in place (the pin’s top should stick out, but the tube edge prevents it from popping out).

- Ensure the end plate is flush against the rear of the receiver but note the takedown pin spring and detent: The rear takedown pin (the smaller pin at the back that holds the receivers together) also has a spring and detent, similar to the front one, but these install from the rear.

- Insert the rear takedown pin now if not already in (it goes through the two holes at the back of the receiver, the flat groove on the pin facing toward the buttstock). Put its detent pin in the little hole at the back of the receiver (just above the buffer tube area on the right side).

- Now when you align the end plate to the receiver, there is a small hole in the end plate that the takedown pin spring sits in. Place the spring in the hole on the end plate, then carefully swivel the end plate in while compressing that spring into the receiver’s channel.

- With the end plate in and the spring captured (held in its hole pressing on the detent), thread the castle nut down to snug the end plate against the receiver.

- Using the castle nut wrench, tighten the castle nut to secure the end plate. Proper torque spec is about 40 ft-lbs. (very snug). For a beginner build without a torque wrench, make it tight and ensure the end plate’s tabs align with the castle nut notches.

- (Expert note: Many builders also stake the castle nut – that is, deform a bit of metal from the end plate into the castle nut notch – to prevent it from loosening. This is military practice. As a beginner, you might skip staking, but do occasionally check the nut for tightness or use a bit of thread locker if not staking.)

- Now insert the buffer spring into the buffer tube from the rear, followed by the buffer itself. Push the buffer in until the buffer retainer pin pops up to lock it. The buffer should now be held in place by that retainer.

- Finally, slide your chosen stock onto the buffer tube. If it’s a collapsible stock, you typically pull down on the adjustment lever to slide it fully on past the retention pin, then let it engage the holes. If it’s an A2 fixed stock, you would have used a different receiver extension; for collapsibles, assume carbine stock. For example, the Magpul MOE-SL stock recommended by many has a strong lock-up and simply slides on and locks in place.

- Adjust the stock to ensure it locks and moves properly.

- Final Lower Checks: Double-check that:

- The safety operates (cannot fire on Safe).

- The magazine catch holds a magazine (you can use an empty magazine to test insertion and release).

- The bolt catch can be pressed and springs back (you can simulate by pressing it while pulling the top of the receiver as if a bolt would press it).

- The takedown pins slide in/out correctly (they should not fall out due to the detents).

- The trigger and hammer function as described in step 5’s function test (do one more dry fire test on Safe/Fire).

- The buffer and action spring move (press the buffer retainer to release the buffer – it should spring out a bit, but not fly because the spring is long; then push it back in).

Congratulations, you have a fully assembled AR-15 lower receiver! For a first-timer, this is a satisfying accomplishment. It’s often said the lower is the “easy half” of the build, but take pride in doing it correctly. A reliable lower with a decent trigger is the foundation for good shooting.

Intermediate: Enhanced Lower Builds

If you have some experience or want to incorporate upgrades into your lower, consider these intermediate-level enhancements and their installation notes:

- Upgraded Trigger: Installing an aftermarket trigger can greatly improve your AR’s feel. Options include drop-in triggers (self-contained units from companies like CMC, Rise, etc.) or component triggers like the Geissele SSA/E two-stage triggers. Many drop-in triggers simply slot into the trigger area and use the same pins (or proprietary pins) to secure. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions. For example, if you find a mil-spec trigger too heavy or gritty, a Geissele SSA-E provides a crisp break and is a popular premium choice. Intermediate builders can handle this as it usually doesn’t require fitting, just attention to safety (some come with adjustment screws – use thread locker if required so they don’t back out).

- Anti-walk Pins: Some triggers come with anti-walk or anti-rotation pin sets. These are pins that lock on both sides so they cannot drift out under rapid fire or vibration. Installation is simple – they replace your standard trigger/hammer pins and secure with small screws or plates. Use a bit of blue Loctite on the tiny screws so they stay put.

- Ambidextrous Safety Selector: If you’re left-handed or want ambi control, you can install an ambidextrous safety. This typically involves replacing the standard selector with an ambi one that comes in two pieces (one for each side, connecting via the center). Install is similar to the standard selector (often you insert one half, then screw on the other half from the opposite side). Ensure the detent and spring engage properly. Some ambi safeties allow changing between 90-degree throw or 60-degree short-throw – configure as you prefer, but note that using a short-throw may require a different detent or selector markings.

- Extended Controls: Intermediate builders might add an extended magazine release button (larger surface) – that simply screws onto the mag catch shaft after assembly (just depress mag catch and unscrew the old button, replace with new oversized one). Extended bolt catches (e.g., BAD lever) can attach to the standard bolt catch to allow dropping bolt from the trigger finger side – attach per instructions (usually a clamp-on piece).

- Enhanced Lower Parts: Some lower receivers (like the Aero M4E1 mentioned earlier) use threaded pins for the bolt catch and rear takedown pin detent, instead of roll pins. If you have such a lower, assembly is actually easier: you’d screw in the bolt catch pin with an Allen wrench instead of hammering a roll pin, etc. Always check if your receiver has any proprietary parts or methods. The guide above assumed a classic mil-spec pattern.

- Sling Attachment End Plate: Instead of a plain end plate, you can use one that has sling attachment points (like QD sockets or loops). Installation is the same, just replace the standard end plate. Be sure to orient any sling loop correctly (facing down or out as you prefer) before torquing the castle nut.

- Tuning Buffer Weight: A bit more advanced but intermediate builders sometimes choose a heavier buffer (H or H2, etc.) to slightly soften recoil or slow the cyclic rate. This can be beneficial if running a suppressor or a mid-length gas system, etc., but too heavy a buffer can cause reliability issues if the gas system isn’t providing enough force. As Aero’s guide suggests, unless you know your setup requires it, sticking to a standard carbine buffer initially is wise. You can always swap buffer weights later (it’s as simple as popping out the buffer and spring and inserting a new one).

- Grip Upgrades: Replacing the standard A2-style grip with something more ergonomic (Magpul MOE, BCM, Ergo, etc.) is very common. This is an easy swap – just unscrew the old grip and screw on the new, making sure the safety detent spring goes into the new grip’s hole. Choose a grip that fits your hand and shooting style; many have storage cores for spare parts or batteries as noted in Aero’s recommendation.

- Trigger Guard: If your lower receiver has a separate trigger guard (some have it built-in as part of the forging), you can swap the flat mil-spec guard for an extended or winter trigger guard (allows more room for gloved fingers). This is a small change but requires removing a roll pin at the front of the trigger guard. Use caution: support the ears of the receiver when punching that pin to avoid breaking them. Many aftermarket trigger guards (Magpul, etc.) include a set-screw for the rear and use the existing front pin or a replacement. Follow their instructions.

Best Practices & Tips (Intermediate): When upgrading parts, maintain compatibility – ensure your trigger pins are .154" mil-spec vs .170" (those larger were for older Colt lowers; almost all modern ones are .154"). Use a tiny dab of grease on trigger sear surfaces for smoother pull (don’t overdo it or the sear could collect debris). If installing a lighter trigger, function test rigorously – ensure the safety works and the disconnector properly catches the hammer during cycling, etc. If something seems off (hammer follows the bolt when you hold trigger – a dangerous condition), do not use the rifle until fixed. Most name-brand triggers will be safe if installed right.

Also, at intermediate level, you might apply some BLUE (medium) Loctite on screws like grip screw, selector lever screw, or castle nut if not staked, to prevent loosening over time – but do not use Red (permanent) as you want to be able to remove these parts if needed. And never Loctite the trigger/hammer pins in place; they should stay via their J-spring or anti-walk devices.

Expert: Advanced Lower Receiver Work

Expert-level work on the lower receiver involves fine-tuning and possibly non-standard builds. Here are some expert topics:

- Precision Trigger Tuning: Rather than buying a drop-in trigger, an expert might polish engagement surfaces of a mil-spec trigger to smooth it out (using very fine stone or polish compound). They might also adjust springs (or use reduced power spring kits) to lighten the pull. Caution: Stoning a sear is delicate – removing too much metal can make the trigger unsafe (prone to slam-fire or not holding at all). Only attempt if you truly understand trigger geometry, and always function test with dummy rounds before live fire. Often, it’s safer to buy a high-quality match trigger that’s been engineered for light pull. For ultimate triggers, brands like Geissele, LaRue MBT, TriggerTech, etc., are popular. Some competitive shooters even install adjustable triggers where you can set sear engagement and reset – these must be tuned carefully and secured with locking screws.

- Short Reset or Binary Triggers: (Legal note: Binary triggers – fire on pull and release – are legal in some states but not others, and the user must be extremely cautious as they mimic full-auto in some ways). Installing these is advanced and beyond our scope, but experts might consider them. Always check legality; for instance, some states explicitly prohibit binary triggers.

- Fitting an 80% Lower: An “80% lower” is an unfinished lower receiver that requires machining to become functional. Some expert builders use these to custom-build firearms without a serial (where legal). Completing an 80% lower involves drilling and milling the fire control cavity and holes – requiring a drill press or milling machine, jigs, and significant skill. It’s truly advanced DIY and nowadays heavily regulated in some jurisdictions (e.g., California requires serialization and registration of 80% builds). If you pursue this, ensure absolute compliance with all laws (we do not cover the milling process here).

- Advanced Lower Components: Perhaps you want to build a caliber conversion that needs different parts – e.g., 9mm AR that uses Colt or Glock magazines. These often require specific lower parts (mag blocks or a dedicated 9mm lower, different buffers, etc.). Or maybe a binary trigger or a custom selector with more than two positions. Experts should refer to specialized guides for these, but the principle of assembly is similar with some extra parts.

- Tighter Fit Upper/Lower: Some expert builders add an “accu-wedge” or tension screw to eliminate play between upper and lower. This doesn’t affect function but gives a tighter feel. Many high-end billet lowers have an adjustment screw in the grip area to push up on the upper for a snug fit.

- Enhanced Buffer System: For example, using a flat-wire spring or a hydraulic buffer for reduced recoil impulse. Installation is same as standard parts, but experts may choose these to fine-tune recoil feel.

- Full-Auto Systems (for licensed individuals): While beyond the scope of this civilian guide (and illegal without expensive licenses/tax stamps), an expert who is an SOT manufacturer might install auto-searers or burst kits. This requires significant modifications and legal paperwork – we mention it only academically. For 99.9% of builders, stick to semi-auto.

- Safety Enhancements: Experts often have a keen eye for safety. For example, verifying the trigger disconnector timing by examining wear patterns, ensuring the hammer and trigger pins rotate freely and don’t walk out under rapid fire (hence using anti-walk pins if needed), and even performing a drop test (unloaded firearm, cocked, on safe – drop from a few inches on a rubber mat to ensure hammer doesn’t drop). A well-tuned trigger can pass these tests.

Expert Best Practices: Always function test repeatedly after any custom tuning. If you stoned your trigger, test it with snap caps – smack the hammer while cocked (with your hand) to see if it slips. Switch the safety on/off, ensure it only fires when supposed to. Use a trigger pull gauge to ensure the pull weight isn’t dangerously light (many consider below ~3 lbs. too light for anything but benchrest use). If you’ve added ambi controls, make sure both sides work correctly (e.g., ambi mag releases shouldn’t drop the mag under recoil – test at range with a few rounds in mag, etc.).

One expert tip for improving a standard trigger without buying anything: a 5¢ trigger job often cited in forums is to dry-fire the trigger a couple hundred times (with snap cap) to let the sear surfaces mate, and/or use a tiny bit of polish on the sear – this can smooth a gritty trigger a bit. Another is using a set screw in the pistol grip screw hole to limit trigger overtravel (though again, advanced modification). Proceed with caution.

Lower Receiver Build Examples – Budget vs. Premium

- Budget Lower Example: You use an Anderson Manufacturing stripped lower ($50) with a basic lower parts kit from Anderson or PSA ($50-70). The mil-spec trigger is ~6.5 lb. pull, a bit gritty but serviceable. Standard M4 collapsible stock and A2 pistol grip (often included in kits) keep costs low. Total cost for the complete lower might be around $150. This basic lower will function fine; many thousands of ARs use these parts. The downside is a heavy trigger and no-frills controls. But it is effective – even stock triggers can achieve good accuracy in practical terms.

- Mid-Tier Lower Example: You opt for an Aero Precision M4E1 forged lower ($120) which has nice features like threaded pins (easier assembly). The lower parts kit you choose omits the trigger because you install a LaRue MBT-2S two-stage trigger ($100, known for excellent value). You add an ambi safety selector ($30) and an enhanced magazine catch and bolt catch (e.g. from Phase 5 or BAD, $50 total). The stock is a Magpul MOE SL (~$60) which is more ergonomic and solid-locking than the basic M4 stock. The grip is a Magpul MOE with storage ($20). Buffer is standard carbine but you use an H2 heavy buffer ($20) to pair with a mid-length gas system for softer recoil. This mid-range lower costs around $350 in parts. It offers a crisp ~4.5 lb. trigger, ambidextrous use, and improved furniture for comfort.

- Premium Lower Example: You use a billet machined lower from a high-end brand (e.g., Seekins Precision or ADM UIC, $250). The trigger is a Geissele SSA-E two-stage ($240) for a superb 3.5 lb. break. Controls are fully ambidextrous: ambi bolt release (built into some lowers or as an addon), ambi magazine release (Norgon or built-in), and a short-throw ambi safety (Radian Talon, $50). Anti-roll pins ($30) secure the trigger. The buffer tube might be a Vltor A5 system ($70) which uses a longer spring and buffer for a smoother impulse; paired with a Magpul PRS stock ($200) for precision shooting or a BCM Gunfighter stock ($60) for tactical use, depending on the rifle’s purpose. Every part is chosen for maximum durability and performance. Cost for this lower setup easily hits $700+. The result is a very smooth-shooting lower with an excellent trigger and fully ambidextrous manipulation – great for competition or duty use. The premium build’s main advantage is the trigger feel and slightly improved ergonomics; it won’t necessarily make the rifle more reliable than a budget build (even cheap lowers can be very reliable) but it can make it more comfortable and effective to operate at a high level.

Regardless of your budget, assembling the lower properly is crucial. Even a high-end trigger won’t help if the lower is put together incorrectly. But with this guide, you should have a rock-solid lower receiver ready to join an upper. Speaking of which, let’s move on to the Upper Receiver Assembly, where we’ll handle the barrel, bolt, and the “boom” side of the rifle.

Upper Receiver Assembly

The upper receiver assembly is the part of the AR-15 that contains the bolt carrier group (BCG), barrel, and other critical components for chambering, firing, and ejecting rounds. This chapter will cover assembling a stripped upper receiver into a complete upper, including the installation of the dust cover and forward assist, barrel and barrel extension, gas block and tube (though gas system specifics are in the next chapter, we’ll physically install them here), handguard, muzzle device, and finally inserting the BCG and charging handle. We will again break it down by skill level:

- Beginner: Many first-time builders may purchase a complete upper, which is fine – you can skip to the next chapter if so. But we’ll still explain the assembly. The beginner approach is assembling a basic upper with standard parts (16” barrel, fixed or low-profile gas block, standard handguard) using mostly drop-in components.

- Intermediate: Upgrading the upper with free-float handguards, better barrels, and understanding headspace checks and proper torque techniques. Possibly assembling upper for a specific purpose (e.g., longer barrel for precision, different calibers).

- Expert: Precision assembly tips such as lapping the receiver face for improved accuracy, using billet uppers, adjustable gas blocks (tuning), and ensuring perfect alignment for long-range accuracy. Also troubleshooting things like ensuring the barrel extension and feed ramps match the lower (e.g., M4 feed ramp cuts) and other advanced concerns.

Parts and Tools Checklist – Upper Receiver

Parts Needed:

- Stripped Upper Receiver: Choose one that matches your lower type (a standard mil-spec flat-top upper is most common). They often come with the forward assist and ejection port cover not installed – we’ll install them. If you got an upper that already has these installed, you can skip those steps. Some uppers are slick-sided (no forward assist or even no ejection port cover), which is fine if you prefer simplicity.

- Barrel: The barrel is the soul of the upper. Common length for general purpose is 16” (legal minimum without going NFA). Barrels come in various lengths (we’ll discuss gas length and performance in the Gas System chapter), profiles (thin, government, heavy), and rifling twists (e.g. 1:7 for heavier bullets, 1:8 or 1:9 for lighter, although 1:7 is a good all-around modern choice). Ensure the barrel comes with an installed barrel extension (most do) which has the locking lugs and feed ramps. Also, many barrels include a pre-drilled hole for the gas pin if using an A2 front sight base.

- Barrel Nut: This might come with your handguard if you are using a free-float handguard system, or if you’re using a standard delta-ring assembly for traditional handguards, it’s a specific type. The barrel nut is what secures the barrel to the upper receiver. Different handguards (free float tubes) often have proprietary barrel nuts.

- Handguard: Either a standard two-piece drop-in handguard (requires a delta ring assembly, often not used in custom builds) or a free-float handguard (KeyMod/M-LOK rails, etc.). Free-float is popular as it can improve accuracy by not binding the barrel and offers more accessory mounting. Ensure your handguard is the correct length to cover the gas system (e.g., a 9” handguard for carbine length gas, 12” for mid-length, etc., or longer if you want it to extend over a low-profile gas block).

- Gas Block & Gas Tube: The gas block attaches to the barrel over the gas port. It can be the traditional A2 front sight base (also serving as a sight), or a low-profile gas block for use under free-float handguards. The gas tube connects the gas block to the upper receiver’s gas key on the BCG. You must use the correct gas tube length (pistol, carbine, mid, rifle) corresponding to your barrel’s gas port position. Gas blocks often come with the appropriate roll pin for securing the tube. Also, note the diameter: most AR-15 barrels are 0.750” at the gas block journal, but some are 0.625” (pencil barrels) or 0.936” (bull barrels) – get the right size gas block.

- Muzzle Device: A flash hider, muzzle brake, or compensator to attach to the muzzle threads (most barrels are threaded 1/2x28 for .223/5.56 barrels). A common default is an A2 flash suppressor. These usually require a crush washer or shims to index correctly.

- Bolt Carrier Group (BCG): The BCG includes the bolt (with lugs that lock into the barrel extension), carrier, gas key (on top), firing pin, cam pin, and retaining pin. You can buy these assembled. Ensure it’s a quality BCG, properly staked gas key screws (they should be staked to prevent loosening) – reputable brands include BCM, Colt, Toolcraft, etc. A bolt should ideally be head-spaced to the barrel – if you mix and match, it’s fine if both are within spec. We’ll talk headspace in intermediate/expert sections.

- Charging Handle: Standard or ambidextrous. It slides into the upper and interfaces with the BCG to charge the weapon.

- Forward Assist assembly: (If your upper uses one) Consists of the forward assist pawl, spring, and roll pin. Often sold as a kit.

- Ejection Port Cover assembly: Includes the dust cover door, hinge rod, spring, and C-clip. Typically comes with the upper or as a kit.

- Misc.: If using a traditional build, you’d need delta ring assembly (delta ring, spring, snap ring) and front handguard cap – but those are only if you use a traditional front sight base and clamshell handguards. Most modern builds with free-float rails won’t use those, as the free-float handguard clamps to a custom barrel nut. We will describe the free-float method, as it’s common for DIY.

Tools Needed:

- Armorer’s Wrench: This is critical for tightening the barrel nut (must fit your specific nut) and often for the muzzle device as well.

- Torque Wrench: Highly recommended to torque the barrel nut to spec. AR-15 barrel nut spec is typically 30–80 ft-lbs.; basically tighten to at least 30 ft-lbs. and then tighten further to align the next notch for gas tube clearance. We will aim ~40-50 ft-lbs. and up if needed for alignment, but not exceeding 80 ft-lbs.

- Vise with Upper Receiver Block: Assembling an upper is much easier with the upper clamped in a vise. Use a specifically designed upper receiver vise block (or reaction rod that locks into the barrel extension) to avoid damaging the receiver.

- Punches and Small Hammer: for the forward assist roll pin and ejection port cover pin if needed.

- Muzzle Device Tools: Often just the armorer’s wrench and torque wrench. A vise helps hold the barrel when torquing the muzzle device. Use appropriate spacer (crush washer).

- Gas Block installation tool: If using an A2 front sight base, you might need a large punch to drive in taper pins. If using set-screw or clamp-on gas block, some thread locker (high-temp) for set screws.

- Lubricant: A bit of light oil or moly grease on barrel nut threads and barrel extension can make torquing smoother and prevent galling.

- Headspace Gauges (optional but recommended for expert): GO and NO-GO gauge for your caliber to ensure the bolt locks properly but not on a no-go (excess headspace). Typically, quality pre-made barrels and bolts are within spec. If you bought both new from reputable sources, they’re usually fine, but checking headspace is a good safety practice if you have gauges.

Now, let’s assemble the upper:

Beginner: Upper Receiver Assembly Step-by-Step

- Install Ejection Port Cover: It’s easier to do this first while the upper is empty.

- Locate the ejection port cover door, hinge pin/rod, spring, and C-clip.

- On the upper receiver, note the two small loops on the right side for the cover. The pin passes through them and the door’s hinge.

- Begin by sliding the rod a couple of inches through the front loop of the receiver. Then place the cover door in position (align its hinge with the loops).

- Insert the spring: The small ejection port cover spring has two legs—orient it so one leg will press against the receiver and the other against the cover door. Hook one leg on the door and one on the upper (you rotate the spring 180 degrees from its relaxed state to tension it). A trick: insert the spring onto the rod when the rod is partway, then rotate the spring so it locks in place (cover should want to spring open).

- Once spring is in, push the rod through the rest of the way, capturing the cover and spring. The rod might have a groove at the end; secure it with the tiny C-clip on the rod’s end on the forward end to keep it from sliding out. (Careful, that clip is tiny and can fling off; cover with finger when snapping it on).

- Test the door: It should freely open (springing fully open) and close (snapping shut with the detent on the door catching the receiver).

- Install Forward Assist (if applicable): (Skip if your upper has no assist or it’s pre-installed).

- The forward assist assembly goes on the upper’s cutout on the right rear. It typically includes the assist plunger, spring, and a small roll pin that secures it.

- Insert the spring onto the forward assist plunger. Push the plunger into its hole on the receiver (you’ll see an aligning flat or tooth that engages the notches on the inside).

- While pressing the forward assist in (you’ll feel spring tension), align the holes for the retaining pin. The pin hole runs horizontally through the boss on the receiver and through a notch in the assist plunger.

- Gently tap the roll pin in with a small punch until flush. This locks the forward assist in place.

- Function check: Press the forward assist pawl – it should spring back and you should hear the clicking of the pawl that would engage the BCG’s serrations. If it moves freely and springs out, it’s good.

- Mount Upper in Vise: Secure your upper receiver in the vise using a proper upper clamp or reaction rod. This is crucial for the next steps involving high torque.

- Insert Barrel into Upper: Take your barrel and remove any protective covers. Check that the barrel extension (the steel section with lugs) is clean and the index pin (small protruding dowel) is present at top. Also ensure the upper barrel nut threads are clean.

- Lightly oil or grease the barrel extension and uppers threads.

- Align the barrel’s index pin with the notch in the upper receiver’s barrel receptacle (it only fits one way, ensuring correct alignment). Push the barrel fully into the upper until it seats – the index pin in the slot and the extension flush with the upper.

- Slide the barrel nut over the barrel and thread it onto the upper receiver threads by hand.

- If using a standard barrel nut (like for a GI delta ring), you’ll also have the delta ring assembly to put on before the nut (slip delta ring, then spring, then snap ring onto barrel before threading nut). If using a free float handguard’s proprietary nut, use what the manufacturer provided.

- Hand-tighten the barrel nut.

- Torque the Barrel Nut: Attach the armorer’s wrench to the barrel nut. Connect the torque wrench to the wrench (if not integrated). The goal is to torque to at least 30 ft-lbs. and then align for the gas tube path.

- Tighten the nut to about 30 ft-lbs. (if you have a calibrated wrench). Loosen it. Then tighten again to, say, 40-50 ft-lbs. The common practice is to tighten-loosen 2–3 times to smooth out threads, then do a final torque.

- On the final torque, go to the minimum where a gas tube hole in the nut aligns with the upper’s gas tube channel (the top of receiver). If you hit 50-60 ft-lbs. and it aligns, stop there. If not yet aligned, you may go a bit more, up to 80 ft-lbs. max. Do not exceed the max or you risk damaging threads or over-stressing. Usually, you’ll find an alignment around 50-70 ft-lbs.

- When aligned, the barrel nut notches (or holes, depending on style) will allow the gas tube to pass through into the upper’s receiver hole easily.

- If using a proprietary handguard nut, follow their torque spec (e.g. Aero’s ATLAS rail nut is 35-65 ft-lb range, others might be similar). Align any special indexing as per instructions.

- Install the Gas Block and Gas Tube: (Some might consider this part of the “Gas System” chapter, but physically it’s done now.)

- First, locate the gas port on your barrel (a small, drilled hole on top of barrel). The gas block must line up with this. Many barrels have a dimple on the underside for set-screw gas blocks – that dimple corresponds to proper alignment for one of the screws.

- If using a standard A2 front sight base (FSB) with taper pins: that typically requires the pins to be hammered in, and alignment is ensured by the pins/barrel holes. This is more advanced and often the FSB comes pre-pinned. If you have that, you likely would have installed it before the barrel nut, including the handguard cap. Beginners usually use low-profile gas blocks instead.

- For a low-profile gas block: Slide the gas block onto the barrel (don’t forget to slide on any handguard cap first if you’re using 2-piece handguards). Ensure the gas block’s hole aligns with the barrel’s port. The block usually has a small hole where the gas tube fits – that should be on top, aligning with the barrel port on top.

- Insert the gas tube into the gas block (if not already). Orientation: the gas tube has a small roll pin hole near the end that goes in the gas block, and the other end (with a slight bend/drop) goes into the upper receiver. The open end of the gas tube (where gas enters) faces the gas port inside the block.

- Once the gas tube is in the block properly (check that the small hole in the tube aligns with the pin hole in the block), tap in the tiny gas tube roll pin to lock the tube to the block.

- Now slide the gas block assembly fully onto the barrel journal, aligning over the gas port.

- Alignment tip: You can look through the upper receiver and peer down the barrel’s gas hole to see if the gas tube is centered in the receiver’s hole (or use a thin rod through the gas tube path to feel alignment). If the barrel has a dimple, align the set screw with that.

- Tighten the gas block. For clamp-on styles, tighten the clamp screws evenly. For set-screw styles, apply blue Loctite if desired (some avoid Loctite due to heat; others use Rocksett if extremely hot environment, but usually blue Loctite is fine up to a point – note Aero warns thread locker can void some warranties on gas block screws). Then torque the set screws snug (~25 inch-lbs. common).

- If you have a pinned FSB, you’d drive in the taper pins from the small end, usually right to left.

Now the barrel with gas block and tube is installed. The gas tube should protrude into the upper receiver through the barrel nut and into the upper, stopping at the gas key area. Make sure the gas tube is centered in that channel and not binding.

- Install the Handguard: This will vary depending on type:

- For a free-float handguard (keymod/M-LOK tube style): Typically, it slides over the barrel and gas block and indexes either via a locking collar or alignment tabs with the upper. Commonly you must align the rail with the upper receiver rail. Some use screws to pinch onto a barrel nut, others thread on.

- Example: A typical free-float like a Midwest Industries or BCM rail uses a proprietary barrel nut (installed already) and then the handguard slides on and is secured by 2-4 screws that clamp it to the nut. Simply slide it so the top rail is flush with the upper’s rail and tighten those screws to specified inch-lbs. (often ~40-50 inch-lbs., sometimes with thread locker).

- If using the classic delta ring and 2-piece handguards: slip the triangular handguard cap over gas block before installing it, then after gas block pinned, pull down the delta ring spring and insert the two handguard halves. This can be tricky but is a known process. Since most new builds go free-float, we won’t detail that heavily.

- Ensure any anti-rotation set screws or tabs on the handguard are engaged properly to prevent it from rotating under use.

- After securing, the handguard should be solid, no movement, and the top rail aligned evenly with the receiver’s rail (if it has a top rail).

Upper Receiver Group Parts Ready for Assembly. In this image, an upper receiver is shown with major components: barrels of different lengths (top and bottom), a free-float handguard (mounted on the upper), a bolt carrier group (right), and muzzle devices (flash hider and brake). These parts will come together in the upper assembly. Free-float handguards like the one shown cover the barrel and improve accuracy by not exerting pressure on it.

- Install Muzzle Device: Almost done – now attach your muzzle device to the threaded muzzle.

- Most AR barrels have 1/2x28 threads. Put the crush washer on first (dome side toward the muzzle device, flat side against the shoulder of barrel). Thread the muzzle device on by hand until hand tight against the washer.

- Now, orient the muzzle device correctly: for an A2 flash hider, the closed bottom should be down (to reduce dust signature). For brakes/compensators, position their ports as instructed (often evenly, or specific orientation).

- Use the armorer’s wrench (which typically has slots for common muzzle devices) or an appropriate size wrench on the device’s wrench flats. Tighten the device further until it times correctly (the crush washer will deform to allow it). Usually, you tighten about 1/4 turn (maybe to ~15-20 ft-lbs.). Do not over-crank it; if it’s not lining up, you can back off and try a new crush washer or shim kit which gives finer control.

- If using a torque wrench on a muzzle device (not critical to exact number as with barrel nut), just ensure it is snug and properly indexed.

- Note: Some devices use shims instead and specify a torque (like 20-30 ft-lb) – follow those instructions if so. Also, if you plan to frequently swap muzzle devices (or attach suppressors), you might avoid crush washers (they are one-time use typically) and use shims or a locking device.

- Install Charging Handle and Bolt Carrier Group: Now that the upper’s hard assembly is done, insert the operating parts:

- Take your charging handle, depress its latch, and insert it into the upper’s groove from the rear about an inch. You’ll feel it fall into a channel.

- Take the assembled BCG (ensure it’s oiled). It’s good to do a quick field strip check: confirm the bolt’s gas rings are staggered (they rotate on their own, so not super critical, but ensure they’re not aligned). If you have headspace gauges, this is where you would remove the bolt from carrier, clean chamber, and check that the bolt closes fully on a “GO” gauge and does not close on a “NO-GO” gauge for your caliber. Most new parts are fine, but experts check anyway for safety.

- Pull the bolt out to the extended position (so it can lock into barrel) and insert the BCG into the upper, underneath the charging handle. The gas key on the BCG fits into the slot of the charging handle. Push them together all the way forward.

- The charging handle should latch, and the BCG should seat with the bolt locking into the barrel extension lugs. If you press the forward assist now, it should engage the BCG’s serrations and help push it (though if properly assembled, it should already be fully forward).

- Now your upper is fully assembled and functional.

- Join Upper and Lower Receivers: Align the upper with the lower, hinge them together by inserting the front pivot pin through the upper’s lug. Then swing the upper down and push in the rear takedown pin. Now you have a complete AR-15!

- Do a basic function check again: Charge the weapon (pull charging handle, let bolt go forward on empty chamber) – the bolt should lock by the hammer. Put on Safe, pull trigger – nothing should happen. Put on Fire, pull trigger – you should hear the click of hammer drop (again, do this with no ammo and preferably snap cap if dry firing often). Hold trigger, rack the bolt (cock hammer), release trigger – you should hear the reset click, then you can fire again. Also insert an empty mag and pull bolt back – it should lock open on the empty mag; drop mag, the bolt catch should hold it, then release bolt catch to close.

For a first-time builder, assembling the upper is the most challenging part due to the barrel nut torque and gas system alignment. Take your time, use proper tools, and don’t hesitate to ask a knowledgeable friend or reference more videos if uncertain. Brownell’s’ video series is a great reference – for instance, their guide cautions on common mistakes in upper assembly and how to avoid them. Key points: ensure proper torque on the barrel nut, correct gas tube alignment, and proper staking of the BCG’s gas key (usually pre-done by manufacturer).

Intermediate: Enhanced Upper Builds

Upgrading or tweaking the upper assembly for improved performance is a natural next step once you understand the basics. Here are intermediate considerations:

- Free-Float Handguard (if not already done): We mostly covered free-float above since it’s common. If you built a basic upper with a clamshell handguard and FSB, an intermediate upgrade is to free-float the barrel. This could mean swapping the delta ring/barrel nut for a new free-float handguard system. The benefit is improved accuracy and more modular accessory mounting. Ensure the free-float handguard is rigid and of good quality (e.g., BCM, Midwest, Geissele rails) for best results.

- Better Barrel Selection: An intermediate build might choose a barrel tailored to purpose. For example, a chrome-lined mil-spec barrel for durability in a defense carbine, or a stainless-steel match barrel for precision shooting. Barrel quality greatly influences accuracy. A premium barrel (e.g., from Criterion, Faxon, White Oak) can shrink group sizes, especially with good ammo. Also consider twist rate and chamber – 5.56 NATO vs .223 Wylde (Wylde is a popular compromise that safely fires 5.56 but can have match accuracy with .223). Intermediate builders also consider different calibers: you could build an upper in 300 Blackout, 6.5 Grendel, etc., for different uses, as long as you have the correct bolt and barrel for that caliber.

- Muzzle Device Upgrades: Swapping the basic flash hider for a muzzle brake or compensator can reduce recoil and muzzle climb. The trade-off is more noise and flash to the sides. Intermediate users try devices like BCM Gunfighter comp, VG6 Precision brakes, etc., to stay on target faster. Installation as described before. Always re-check timing when using new washers/shims.

- Gas System Choices: While the physical installation is the same, intermediate builders might choose a different gas system length or an adjustable gas block. For example, if building a 18” barrel rifle, using a rifle-length gas system can yield a smoother recoil impulse than carbine length (gas port further out = lower pressure at action). Adjustable gas blocks allow you to tune the amount of gas for reliability vs recoil (especially useful if running a suppressor which adds backpressure). Installing an adjustable block is the same, but then you’ll adjust the screw at the range to dial in just enough gas for function. Keep in mind to lock the adjustment if required (some have detents, others might use lock screws).

- Headspace Check: We touched on headspace – intermediate builders should, if possible, check headspace with proper GO/NO-GO gauges, especially if using a bolt and barrel from different sources. Most manufacturers produce within tolerances, but it’s an extra safety step. If a bolt won’t close on a GO gauge, that’s a problem (chamber too tight). If it closes on a NO-GO, that’s a bigger problem (chamber too loose/excess headspace – unsafe). A Field gauge is even longer; if it closes on that, it is definitely unsafe to shoot. In practice, new barrels and bolts rarely have a headspace issue, but it’s wise to check or have a gunsmith check.

- Bedding/Lapping the Upper Receiver Face: A technique to potentially improve accuracy is to lap the front face of the upper receiver (where the barrel extension seats) to ensure it’s perfectly square and flush with the barrel extension. This can increase consistency of barrel harmonics and improve accuracy marginally. Brownells sells a lapping tool for this. To do it, you remove the barrel, insert the lapping tool with abrasive, and turn it to grind the face true. This is intermediate/expert because you are removing a tiny bit of material. Only do it if you suspect misalignment or are chasing max accuracy. Caleb from Brownells notes it may not be necessary on modern quality uppers, but it doesn’t hurt if done carefully.

- Enhanced Bolt Carrier Group: While any mil-spec BCG will do, intermediate builders might choose features like MPI/HPT tested bolts (Magnetic Particle Inspected/High Pressure Tested) for assurance of strength, or coatings like Nickel-Boron or Nitride for smoother operation and easier cleaning. Some BCGs have things like forward assist cuts (almost all do) and improved extractors (springs or O-rings for reliability). Upgrading the extractor spring (e.g., adding an O-ring booster) on a standard bolt is a simple tweak for better extraction if running under harsh conditions (common in carbine-length gas 14.5-16” guns).

- Charging Handle Upgrade: An ambidextrous charging handle (like Radian Raptor or BCM Gunfighter) makes weapon manipulation easier, especially under optics or if left-handed. Installation is the same; they just drop in. They often have better latches and reduce the risk of gas in face when suppressed.

- Precision Upper Assembly: If building a DMR/precision upper, intermediate steps include making sure the barrel nut is torqued and possibly loosened and re-torqued a few times to relieve stress, using some rocksett on gas block screws to handle heat, and aligning the handguard very straight for use with iron sights or lasers (if your handguard has a top rail continuing the receiver rail, ensure no cant or gap).

- Accessory Mounting: Intermediate builders plan the upper with accessories in mind: If you’ll mount backup iron sights (BUIS), pick ones that fit with your setup (gas block height vs rail height issue – a front sight on an actual gas block that’s lower than rail needs a taller sight or just use rail-mounted sights on a free-float). If using optics, think about rail space and eye relief – maybe go with a continuous top rail handguard for flexibility.

Best Practices (Intermediate Upper): Remember to always re-check the tightness of anything screwed on after the first few shooting sessions. Barrel nuts seldom loosen if properly torqued and often staked or held by gas tube, but handguard screws should be checked (use a paint pen witness mark). Muzzle devices should be snug; if using suppressors, consider using Rocksett (high-temp thread locker) on the muzzle device threads so it doesn’t unthread when removing a tight suppressor.

Also, note how your brass ejects when you test-fire: classic AR ejection pattern is 3-4 o’clock. If you see it blasting forward 1-2 o’clock, your rifle might be over-gassed (common in carbine gas barrels) – an adjustable gas block or heavier buffer could help. If it’s dribbling out at 5 o’clock, might be under-gassed or too heavy a buffer. These are fine-tuning items for intermediate builders to diagnose and correct for optimal performance.

Expert: Advanced Upper Receiver Work

For those aiming to build a top-tier upper or specialized configurations, here are expert-level considerations:

- Match-Grade Assembly Techniques: In addition to lapping the receiver face as mentioned, some expert builders will “bed” the barrel extension to the receiver. This can be done with things like Loctite 609 or 620 (a retaining compound) applied lightly on the barrel extension before torquing the barrel nut. The idea is it fills any microscopic gaps and retains the barrel in the same position shot to shot. The Brownells guide mentions barrel bedding may not be necessary if things fit well, but some precision builders still do it. If you do, use only a little so you can remove the barrel later if needed (or heat to break the compound).

- Cryo or Stress Relief: Some high-end barrel makers cryogenically treat barrels for stability. As an expert assembling a super precision rifle, you might seek barrels with this treatment. Not something you do during assembly, but a choice when buying barrel.

- Gas System Tuning & Suppressor Ready Builds: If you plan to run a suppressor often, experts will often incorporate an adjustable gas block or a gas regulator like the Bootleg adjustable BCG or Gemtech suppressed bolt carrier. Tuning the gas to your specific ammo and suppressor can smooth out operation. This is an expert endeavor because you might be adjusting settings for different conditions. Also, choosing the right buffer and spring combination goes together. Some experts use adjustable gas keys or gas tubes (with vents) for fine tuning as well.

- Extended or Alternative Uppers: Expert builders might experiment with non-standard uppers like side-charging uppers (which require different BCG or modifications). They might also build left-handed ARs (Stag makes left-ejecting uppers) for lefty shooters – requiring left bolts, etc.

- Barrel Accuracy Tips: For ultimate accuracy, consider fluting (order a barrel that’s fluted for rigidity and cooling weight reduction), using a longer gas system than normal if possible (e.g., intermediate gas on an 18” instead of mid-length, to further soften pressure), and quality ammo. A great upper can only shine with good ammunition – experts tend to handload or buy match ammo for their precision AR builds.

- Caliber Conversions: Building AR-15 uppers in calibers like 6.5 Grendel, .224 Valkyrie, 6.8 SPC, etc., might be an expert pursuit. Each has nuances (bolt strength, magazine types). Always use the correct bolt and magazine for the caliber. For example, 6.5 Grendel needs a Grendel bolt (different face size) and perhaps an enhanced firing pin protrusion. Research each caliber thoroughly – beyond scope here.

- Muzzle Device Timing for Recoil Control: An expert might tune the exact timing of a compensator to account for their shooting style. For instance, some brakes allow you to clock them slightly to counteract your personal pull or stance if rifle recoils off-center. This is really fine-tuning. It might involve trial and error at the range, shimming, and re-testing.

- Optics Mounting (in context of upper): Not assembly of the upper per se, but experts building a rifle will pay attention to how they mount optics on the upper. Using one-piece cantilever mounts torqued to spec (typically like 20-25 in-lbs. on rings, 30-65 in-lbs. on rail clamp depending on manufacturer). Lapping scope rings if necessary to ensure no stress on the scope tube. Leveling the scope properly, and possibly bedding the scope mount if extreme precision (rarely needed with quality mounts). This bleeds into the optics chapter, but it’s part of the full upper’s performance potential.

- Quality Checklist: Experts will inspect everything: gas block alignment (maybe using a bore scope to see the port alignment), even measure headspace if they have gauges each time they swap a bolt, check that the bolt lugs all bear properly (using marking compound to see contact patterns), and polish feed ramps if there are burrs (if, say, a mismatch between upper and barrel extension feedramps leaves a sharp edge, one might lightly smooth it). These fine details can improve reliability in harsh conditions or with mixed ammo.

- Troubleshooting During Build: If an expert cycles dummy rounds through the assembled upper/lower and notices, for example, bolt won’t lock back or feed issues, they will troubleshoot before even going to live fire. Check alignment of gas tube (BCG should slide in freely without gas key binding on tube – if binding, adjust tube alignment slightly by re-centering gas block or tube bend). Check that ejector can push rounds out (some experts polish the ejector to ensure smooth movement, or slightly bevel the edge of ejector to better slip past case rim – not usually needed, but a tweak). Check extractor tension (add O-ring if extraction seems weak).

- Documentation & Data: True experts treat each build scientifically – they might keep a log of torque values they used, lot numbers of parts, and then how the rifle performs (groups, velocities, malfunctions). This helps refine future builds. For instance, if a certain barrel nut torque yielded best accuracy in one build (some claim slight differences can show up in group sizes), they note it.

Upper Receiver Build Examples – Budget vs. Premium

- Budget Upper Example: A basic upper might use a PSA (Palmetto State Armory) 16" barrel (5.56 NATO, chrome-moly steel) with a carbine-length gas system and an A2 front sight base. The handguards are standard M4 two-piece plastic. The BCG is a standard phosphated mil-spec from PSA or Toolcraft. Charging handle is basic. Muzzle device is A2 flash hider. This could be assembled by buying a kit or separate parts totaling approximately $300-400 for the upper. It’s a no-frills, serviceable upper with acceptable accuracy (~2-3 MOA with good ammo) and full reliability. It mirrors a military M4 style. Weight is a bit more due to the clamshell handguard and FSB, but it’s robust. Pros: inexpensive, proven design. Cons: not as modular (fixed FSB limits optic mounting unless using a carry handle or adding railed handguard), and recoil may be a bit sharper due to carbine gas.

- Mid-Tier Upper Example: An intermediate build could use an Aero Precision forged upper ($80) with a 16" mid-length chrome-lined barrel from Ballistic Advantage or FN (~$200). Mid-length gas gives a smoother recoil impulse. Use a low-profile gas block ($30) and a free-float M-LOK handguard, say a 13" Aero Atlas S-One handguard ($150) which is lightweight. The BCG might be a nitride-coated model from Faxon or BCM ($150) for durability. Add a BCM Gunfighter charging handle ($50). Muzzle device: a VG6 Gamma brake ($70) for better recoil control. This mid-tier upper costs around $600-700. It offers improved accuracy (~1.5-2 MOA) and shootability. The free-float rail allows mounting lights, lasers, whatever accessories easily. It’s a great general-purpose upper for defense or competition. Pros: softer recoil, more accuracy, modular. Cons: higher cost, muzzle brake is louder to shoot.

- Premium Upper Example: Here we pull out all stops. Consider a VLTOR or Larue billet upper receiver ($200+) for precision alignment. The barrel could be an 18” stainless match-grade barrel from White Oak Armament or Criterion ($300) for long-range accuracy, with a rifle-length gas system. Use a Geissele or Midwest URR barrel nut and a 15” Geissele MK16 free-float rail ($300) known for rigidity. The gas block would be an adjustable type, like Superlative Arms ($100), to fine-tune the rifle’s cycling. BCG could be a high-end one like Young Mfg. National Match chrome BCG ($250) or a precision lapped one. Charging handle may be a Radian Raptor ambi ($80). Add a SureFire WarComp muzzle device ($150) that doubles as suppressor adapter. This upper might cost $1200+. It’s built for accuracy <1 MOA and/or for use with a suppressor (hence adjustable gas). Pros: maximum accuracy and very refined recoil and component quality. Cons: diminishing returns on cost – you pay double for a 10-20% performance gain. Also, a precision stainless barrel may be heavier and a bit less long-life than chrome-lined.

Between these extremes, you can mix and match to meet your budget and goals. Often a good strategy is to invest most in the barrel and BCG – those affects shooting the most – and you can economize on things like handguards or stocks which can be upgraded later easily. For example, even a budget upper with a quality barrel can shoot excellently.